3. The Gravitational 2-Body Problem

A decision was made to let Carol take the controls, for now. Taking

the keyboard in front of a large computer screen, she opens a new file

nbody.rb in her favorite editor. Expectantly, she looks at Erica,

sitting to her left, for instructions, but Dan first raises a hand.

Dan:

I'm a big believer in keeping things simple. Why not start by coding up

the 2-body problem first, before indulging in more bodies? Also, I

seem to remember from an introductory physics class for poets that the

2-body problem was solved, whatever that means.

Erica:

Good point. Let's do that. It is after all the simplest case that is

nontrivial: a 1-body problem would involve a single particle that is

just sitting there, or moving in a straight line with constant velocity,

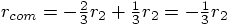

since there would be no other particles to disturb its orbit.

And yes, the 2-body problem can be solved analytically. That means

that you can write a mathematical formula for the solution. For

higher values of N, whether 3 or 4 or more, no such closed formulas

are known, and we have no choice but to do numerical calculations in

order to determine the orbits. For

Yet another reason to start with

Dan: A one-body problem? You mean that one body is fixed

in space, and the other moves around it?

Carol: I guess that Erica is talking about a situation where one body

is much more massive, so that it doesn't seem to move much, while the

other body moves around it. When the Earth moves around the Sun, the

Sun can almost be considered to be fixed. Similarly, when you look at

the motion of the Moon around the Earth: the Earth has a much larger

mass than the Moon, and the mass of the Sun is again much larger than

that of the Earth.

Erica: Yes, a large mass ratio makes things simpler. In that case we

can make the approximation that the heavy mass sits still in the center,

and the lighter mass moves around it. But that is only an approximation,

and not completely accurate. In reality, both masses move around each

other, even though the heavier mass moves only a little bit.

Even for the case where the masses are comparable, we can still talk

about the relative motion between the two particles. And we don't

have to make any approximation. Here, let me draw a few pictures, to

make it clear.

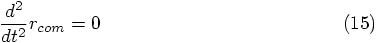

3.1. Absolute Coordinates

, we have the

luxury of being able to test the accuracy of our numerical

calculations by comparing our results with the formula that Newton

discovered for the 2-body problem.

, we have the

luxury of being able to test the accuracy of our numerical

calculations by comparing our results with the formula that Newton

discovered for the 2-body problem.

is that the

description can be simplified. Instead of giving the absolute

positions and velocities for each of the two particles, with respect

to a given coordinate system, it is enough to deal with the

relative positions and velocities. In other words, we can

transform the two-body problem into a one-body problem, effectively.

is that the

description can be simplified. Instead of giving the absolute

positions and velocities for each of the two particles, with respect

to a given coordinate system, it is enough to deal with the

relative positions and velocities. In other words, we can

transform the two-body problem into a one-body problem, effectively.

.

.

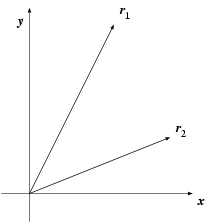

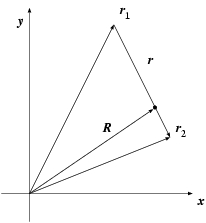

Carol: But in order to define those vectors, you first have to choose a coordinate system, right?

Erica: Yes. We have to choose an  axis and a

axis and a

axis, and they together make up a coordinate system.

The point of intersection of the two axes is called the origin of the

coordinate system. With respect to the origin, the positions of the two

bodies are pointed out by the tips of the arrows that stand for the two

vectors

axis, and they together make up a coordinate system.

The point of intersection of the two axes is called the origin of the

coordinate system. With respect to the origin, the positions of the two

bodies are pointed out by the tips of the arrows that stand for the two

vectors  .

.

Dan: I see the vectors, but I don't see the bodies.

Erica: You have to imagine the bodies to reside at the very end of each arrow.

Carol: They are point masses, remember, so they are too small to see!

Erica: Well, yes, but of course I could still have drawn them as small points. However, I wanted to keep the figures simple.

Dan: What would happen if you had chosen a different coordinate system?

Erica: In that case, the tips of the arrows would stay at the positions

of the particles, since they would not change. However, the arrows

themselves would change, because they would be rooted in the new origin.

Dan: But could you really have chosen any coordinate system?

And could you then let it change or rotate or let it jump up and down?

That seems rather unlikely.

Erica: Ah, no, certainly not. Or more precisely, preferably not.

If you choose a coordinate system that moves in a strange way, you

then have to correct for those strange motions of the coordinate axes,

which would be reflected in the description of the motions of the

particles. And you would then have to correct for that, in the

equations of motion.

Carol: I'm not sure I follow all that, but I guess the upshot is that

you want to keep things simple, and therefore you prefer to use coordinates

where the origin stays at rest in space.

Erica: Yes, either at rest, or otherwise the origin should move at a

constant speed in one fixed direction. A coordinate system that moves

in such a way is called an inertial coordinate system. By the way, we

use the term uniform motion for the type of motion that occurs

at constant speed in the same direction.

Dan: Ah, that is a term I remember from my physics class. This is related

to the fact that Newton discovered that an object which does not feel any

forces will keep moving in a straight line with constant speed. Because

of the inertia of an object, you have to exert a force in order to change

that type of motion.

Erica: Indeed. And this means that any object that feels no force will

move in a straight line at constant speed in any inertial coordinate system.

But if you start with, for example, a rotating coordinate system, then even

an object at rest seems to rotate in the opposite direction, when you describe

its motion with respect to the rotating frame.

Dan: And all of this is related to Newton's concept of absolute space,

right? And Einstein showed that there is no such thing as absolute space.

Erica: The idea of an absolute space was a brilliant invention, very

useful to describe the phenomena on the level of classical mechanics.

But when you deal with high velocities, approaching the speed of light,

or even with lower velocities and very high accuracies, you have to take

into account the fact that special relativity gives a more accurate

description of the world.

Carol: And general relativity is even more accurate, I presume?

Erica: Yes, but in general relativity space and time are curved,

in a way that is influenced by the distribution of masses and energy

in the world. This means that it is extremely difficult to make a

computer simulation of the motion of objects such as black holes when

they approach each other.

Dan: I'm happy to keep things simple, for now at least, and to stick

to Newton's classical mechanics.

Carol: So am I.

Dan: Okay, I got the picture. Now where does the one-body representation

come in?

Erica: It comes in through a clever coordinate transformation.

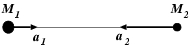

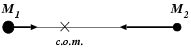

The trick is to add a fourth point to the picture given in

fig. 5, besides the origin and the positions of

the two particles. The extra point is what is called the center of

mass of the system, often abbreviated to c.o.m. for simplicity.

Dan: You mean the point right in the middle of the two masses?

Erica: No, not if the particles have different masses. Here is the

basic idea. Let me draw two masses at rest, in fig. 6.

Let particle number 1, at the left, be twice as massive as particle 2,

at the right:

Dan: I hope it will be sooner!

Erica: In this very simple example, let us define the

Carol: Where is the origin?

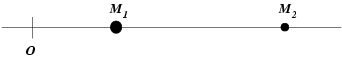

Erica: You can put the origin anywhere you want. For example, if you

like to put it to the left of

Figure 7: Two bodies at rest, with the origin O of a one-dimensional coordinate system

shown at the left.

Dan: Yes, I can see that as long as O stays to the left of both particles.

But how about the other cases? Let's check. If we take O to be at the

right, then the two particle positions have negative values, with

The last possibility is to have O located right in between the two particles.

In that case,

Erica: In any of the tree cases that you just explored, the force that

particle 1 feels from particle 2 is:

In contrast, particle 2 will be pulled to the left, and it will start

to move with a negative velocity, so its acceleration is negative.

Other than this important minus sign, we can simply reverse subscripts

1 and 2, which gives:

Carol: Action equals reaction, that's one of Newton's laws, right?

Erica: Right indeed, that is Newton's third law. Now let us use

Newton's second law, to see how the particles will actually start

moving. His second law is the famous

If we use these relations with Eqs. (1, 2), we find

Dan: That makes sense. It takes twice as much force to move a particle

that is twice as massive.

Carol: And this means that the two particles start falling toward

each other at different rates, and therefore they will not meet in the

middle.

Dan: They will meet closer to particle 1. In fact, because particle 2

will always be accelerated twice as fast as particle 1, I bet they will

meet at a point that is one third of the way over, going from 1 to 2.

Carol: Could that be the fourth point that you talked about, Erica,

what you called the center of mass?

Erica: Yes, indeed! The center of mass, c.o.m., in the case of the

two-body problem, is the point of symmetry, around which each of the

two bodies moves in a way that is inversely proportional to their mass.

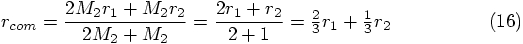

As I remember it, the position of the c.o.m. is given by

Dan: No, I don't see that. Adding the right hand sides does not give zero.

Carol: Ah, but multiplying the first equation by

Carol: Erica, correct me if I'm wrong, but I think what it means is

that the attractive gravitational forces that the two particles exert

on each other are balanced: equal but opposite in direction. For my

own peace of mind, let me summarize what I think has happened so far.

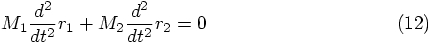

Eq. (1) is Newton's gravitational equation, and so is

Eq. (2), while (3) and (4) express Newton's law

connecting force and acceleration. Combining both of these Newtonian

laws allows us to write (5) and (6) as Newton's

gravitational equations in terms of acceleration rather than force.

After that, (8) and (9) are just rewriting (5) and

(6) in a different notation. Then (12) adds (8)

and (9), showing thereby in a more formal way that the

attractions between the two stars cancel each other. We could have

drawn that conclusion directly from (1) and (2) as

well, but there we would not yet have had the information about the

second derivatives of the positions.

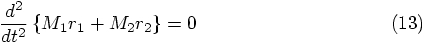

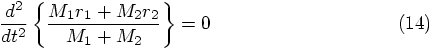

Erica: Yes, that sums it up nicely. And we can write Eq. (12)

as:

Dan: Not so fast, how can you see that?

Carol: You can choose the origin of our coordinates where you like.

Take particle 1 to be the origin, for example, and you will get

Dan: Well, let me try your game too, at a somewhat more complicated

point. Let me put the origin of the coordinates exactly half-way between

the particles. In that case,

Figure 10: Construction of alternative coordinates

Dan: But now you have changed your mind, assuming that particle 2

is heavier than particle 1!

Erica: Why not? These figures should be correct for any choice of

masses. I just didn't want to get stuck with the same simple choice

for all the figures we will draw.

Carol: So far, you have told us what the center of mass is,

but you haven't told us why it is called that way. Looking

again at Eq. (17), it seems that the c.o.m. is the mass

weighted position of an extended object. We use that notion in computer

graphics for computer games all the time. One way to look at it is to

ask yourself where you should support a rod with two weights attached

at the end. If one of the weights is twice as heavy as the other, it

should be twice as close to the support point as the other is, in

order to balance the rod.

Dan: I see, that helps. So with `mass weighted' you mean that I multiply

the position of each particle with its mass, so that more massive particles

have a larger vote, so to speak, in where the center of mass will be.

Carol: Yes, and then you have to divide by the total mass. Already on

dimensional grounds it is clear that you have to divide by a mass, as Erica

told us, to wind up with a result that has the dimension of length.

And in the equal mass case, it is clear that the c.o.m. should be the

average of the two positions, the point right in between them.

Now here is what seems odd.

In fig. 5 the two vectors

In other words, the two coordinate systems do not seem to be compatible.

Erica: Good point. It is true that the information contained in the

pair of vectors

Erica: Yes. Any coordinate system anchored to a particle that

deflected by forces acting upon it cannot be an inertial system.

Dan: So the vectors

Erica: Yes, that is a nice way to split it out. 3.2. Coordinate Systems

3.3. A Fourth Point

. As soon as we let the particles

move freely, from rest, they will start falling toward each other.

. As soon as we let the particles

move freely, from rest, they will start falling toward each other.

axis of our coordinate system to go through both particles, with the

positive side at the right, as usual.

axis of our coordinate system to go through both particles, with the

positive side at the right, as usual.

, as in fig. 7,

then both particles are located on the positive x axis, and

therefore both particles have positive values for their positions

, as in fig. 7,

then both particles are located on the positive x axis, and

therefore both particles have positive values for their positions

and

and  with respect to the origin.

Moreover,

with respect to the origin.

Moreover,  , so the distance between the two

particles is given as

, so the distance between the two

particles is given as  .

.

remains the same, and that's the only thing that counts.

remains the same, and that's the only thing that counts.

further away with a more negative value, say

further away with a more negative value, say

and

and  . In that particular case,

. In that particular case,

. Okay, that gives the

right answer.

. Okay, that gives the

right answer.

is negative and

is negative and  is positive,

and clearly

is positive,

and clearly  is positive as well. Good! I am

convinced now that

is positive as well. Good! I am

convinced now that  is the right expression for

the physical distance between the two particles, with a value that is

always greater than zero, if the particles are not at exactly the same place.

is the right expression for

the physical distance between the two particles, with a value that is

always greater than zero, if the particles are not at exactly the same place.

is the distance between the two particles and

is the distance between the two particles and

is Newton's universal constant of gravity.

Particle 1 is being pulled in the direction of the positive

is Newton's universal constant of gravity.

Particle 1 is being pulled in the direction of the positive  axis. This means that the velocity changes from zero to a positive value,

which in turn means that the acceleration is positive.

axis. This means that the velocity changes from zero to a positive value,

which in turn means that the acceleration is positive.

is the acceleration that particle

is the acceleration that particle  undergoes, due to the force

undergoes, due to the force  .

.

of particle 2 is twice

as large as the acceleration

of particle 2 is twice

as large as the acceleration  of particle 1.

of particle 1.

3.4. Center of Mass

and the second equation by

and the second equation by  gives

gives

, so:

, so:

and then Eq. (16) gives you

and then Eq. (16) gives you

.

Or take particle 2 as the origin, which means

.

Or take particle 2 as the origin, which means  and Eq. (16) gives you

and Eq. (16) gives you  ,

which means at a distance from particle 2 that is two thirds on the

way to particle 1.

,

which means at a distance from particle 2 that is two thirds on the

way to particle 1.

. Now let's see

what Eq. (16) gives me. Aha:

. Now let's see

what Eq. (16) gives me. Aha:

.

What do you know! One third of the way from the origin in the direction

toward particle 1. Exactly the point that is twice as close to particle

1 as to particle 2. Okay, I'm convinced!

.

What do you know! One third of the way from the origin in the direction

toward particle 1. Exactly the point that is twice as close to particle

1 as to particle 2. Okay, I'm convinced!

3.5. Relative Coordinates

and

and

for the center of mass position and the relative

position of the two bodies, respectively.

for the center of mass position and the relative

position of the two bodies, respectively.

value of the position. In the more general

case of two or three dimensions, we have to go back to vector notation.

Eq. (7) in vector form becomes:

value of the position. In the more general

case of two or three dimensions, we have to go back to vector notation.

Eq. (7) in vector form becomes:

as the relative

position of the second particle with respect to the first particle:

as the relative

position of the second particle with respect to the first particle:

.

.

, that define the alternative

coordinate system. Here it is, fig. 11.

, that define the alternative

coordinate system. Here it is, fig. 11.

start

at the same point, namely the origin. But in

fig. 11 only the c.o.m. vector

start

at the same point, namely the origin. But in

fig. 11 only the c.o.m. vector

starts in the origin, while the relative position vector

starts in the origin, while the relative position vector

connecting the two particles does not.

connecting the two particles does not.

is the same as the information

contained in the vector pair

is the same as the information

contained in the vector pair  . But in the first

case, both vectors appear in the same inertial coordinate system, while

in the second case, only

. But in the first

case, both vectors appear in the same inertial coordinate system, while

in the second case, only  is a vector in an inertial

coordinate system, while

is a vector in an inertial

coordinate system, while  points to particle 2 within a

coordinate system anchored to particle 1, which is certainly not inertial.

points to particle 2 within a

coordinate system anchored to particle 1, which is certainly not inertial.

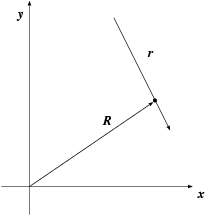

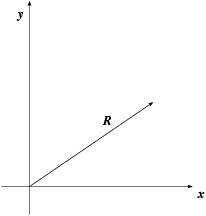

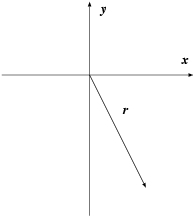

are all defined in the

same original inertial coordinate system, while

are all defined in the

same original inertial coordinate system, while  is defined

in a different coordinate system, which is not inertial. Let me make that

clear, and draw two new figures. Figure 12 shows the c.o.m.

vector in the original coordinate frame, while figure 13

shows the relative separation vector in a different frame, anchored on

particle 1, as you just explained.

is defined

in a different coordinate system, which is not inertial. Let me make that

clear, and draw two new figures. Figure 12 shows the c.o.m.

vector in the original coordinate frame, while figure 13

shows the relative separation vector in a different frame, anchored on

particle 1, as you just explained.

.

.

and

and  .

.

in the inertial coordinate system

in the inertial coordinate system

in a non-inertial coordinate system

in a non-inertial coordinate system