4. A Gravitational 1-Body Problem

Dan: But I'm still confused. You started talking

about a change from absolute to relative coordinates. But in fact we

seem to switch from two vectors in an absolute inertial coordinate

system to two other vectors, one in the old coordinate system and one

in a new, non-inertial coordinate system. What is going on?

Erica: I guess the notation and terminology in physics is rather sloppy.

We generally don't try to be logically precise, the way mathematicians are.

But I'm glad you're forcing us to be clear about our terms. It helps

me, too, to build things up again from scratch.

It seems that there are two ways to use the notion of coordinates.

But let me first summarize what we have learned.

We have, so far, dealt with two coordinate frames. We have the

inertial one, centered on an arbitrary point, a point that is either

at rest or in uniform motion with respect to absolute space. The

coordinate axes point in fixed directions with respect to absolute

space. And we also have the non-inertial frame, centered on particle 1.

And although this frame is non-inertial, because particle 1 feels

the force of particle 2 and therefore does not move in a straight line

at constant speed, the coordinate axes of the non-inertial coordinate

system remain parallel to the coordinate axes of the inertial

coordinate system.

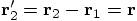

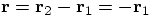

This last point is important. When the two particles complete one

orbit around each other, the relative vector

Now here are the two ways that physicists use `coordinates', at least

as I understand it. The first way is to give the coordinates of vectors

with respect to the coordinate frame in which they are defined. In that

case, we have already dealt with the coordinates of the four vectors

The second way to talk about coordinates is to capture the information

about a whole system, and not just a single particle with respect to

a point in space. We can say that we have described a two-body

configuration completely when we give the information contained in the

pair of vectors

So in the second way of speaking, a coordinate transformation means a

change between describing the two-body system through specifying

In the beginning of our session, I used the second way of speaking.

But then, when we started talking about coordinate systems, I guess

I slipped into the first way of speaking.

Dan: Thanks for separating those two ways of speaking. I'll have to

go over it a few times more, to get fluent in this way of thinking,

but I'm beginning to see the light.

Carol: Now the beautiful thing is: it is possible to use the

same language for both ways of speaking. This is something else I

learned in our `computer game' class as we called it, although it was

really titled as a `geometrical representation' class. If a single

vector lives in a

Mathematically speaking, each choice of a set of two vectors, whether

it is

Dan: Just when I thought I understood something, Carol manages to

make it sound all gobbledygook again. I'll just stick with Erica's

explanation.

Carol: Well, I have one question left. I mentioned that the

transformation between the

I think that is true, but I would like to prove it, to make sure, and

to see explicitly which pair of

Dan: Good questions! Erica has

shown how to derive

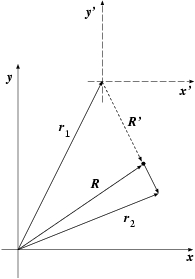

Erica: Yes, we can, or at least I'm pretty sure we can. But we'll have

to scratch our heads a bit to write it down. Let us start with figure

10. We can use the same figure, but now we

should consider

When I took my classical mechanics course, many homework questions

were of this type, and generally they involved a clever form of

coordinate transformation. Hmmm. Let's see. Right now the origin

is at an arbitrary point in space. We could shift to a coordinate

frame that is centered on one of our three special points; the position of

particle 1, the position of particle 2, or the position of the c.o.m.

Well, why not start with particle 1, and see what happens. Let me draw

the new coordinate frame, using primed symbols:

Figure 14: A shift of coordinate frame brings the origin to the position of particle 1.

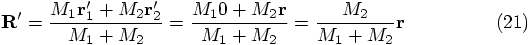

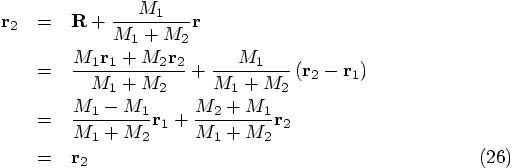

In this new frame, the c.o.m. vector is

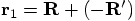

Dan: Wait a minute, not so quick. I don't see that yet. Let me try

to take smaller steps. The vector

So far so good. And this means that we have

Carol: Elementary, my dear Watson. In the old coordinate frame, we

had Eq. (17) which gave us the position vector of the c.o.m. in

that frame. Let's write it again:

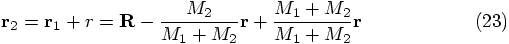

Dan: And the second particle's position is obtained simply by

interchanging the subscripts 1 and 2 everywhere, right?

Erica: Wrong, but almost right: there is an additional sign change.

We can show that in the same way as Carol just did, but putting the

origin now in the position of particle 2. Or, even simpler, we can

look at the picture, which tells us that:

Carol: First, starting with

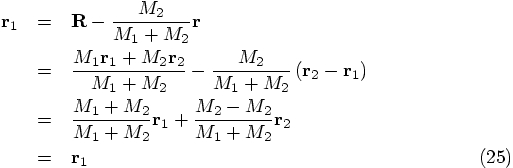

Dan: Let me play the devil's advocate. We are doing science, so

I want to have hard evidence! As you already saw, it is all too easy

to replace a plus sign with a minus sign and stuff like that, so we'd

better make sure we really get things right. Let me try to prove it

my way.

Carol: Prove what?

Dan: Prove that we are consistent, and that we can close the circle

of transformations, from

I will take Eq. (22) and then use the original definitions

Eqs. (17) and (18):

Erica: I agree. Okay, all three of us are happy now. Let's move on!

Carol: Well, we got a new system of relative coordinates. I presume

we're going to use it for something, right?

Erica: Yes, time to rewrite Newton's equations of motion into the new system.

For the one-dimensional case above, we used Eqs. (27) in scalar

form. Let me write it in vector form. So this is the equation for the

acceleration of the first particle, due to the gravitational force

that the second particle exerts on it:

Dan: Glad to hear that! But I'm puzzled about one thing. Why is

there a third power in the denominator? I thought that

gravity shows an inverse square attraction, not an inverse cube!

And after all, that was what we wrote in Eq. (27).

Erica: Yes, the magnitude of the acceleration is indeed proportional

to the minus second power of the separation. However, we also need to

indicate the direction of the acceleration. We can define a unit

vector

Carol: I guess that Erica wrote it in the form of Eq. (27)

because it will be easier to program that way.

Erica: Indeed. Once you get used to this way of writing the equations

of motion, there is no need to introduce the new quantity

Let me also write the acceleration for the second particle:

Dan: Hmm, I'm still a bit confused about these signs. When the force

points to the first particle, why does that imply a minus sign?

Carol: The easiest way to see this is to take a particular case. Imagine

that the second particle is positioned in the origin of the coordinates.

Since gravity pulls particle 2 in the direction of particle 1, the

acceleration that particle 2 experiences points in the direction of

Dan: Ah, that is neat. Instead of trying to figure things out in

full generality, you take a particular limiting case, and check the

sign. Sort of like what Erica did, in constructing here a primed coordinate

system. Since you already know the magnitude and the line along which

the acceleration is directed, once you know the sign in one case,

you know the sign in all cases.

Carol: Yes. Technically we call this invariance under continuous

deformation. If you bring the second particle a little bit out of the

origin, by small continuous changes, the acceleration between the

particles must change continuously as well; it cannot suddenly flip

to the opposite direction.

Erica: Neat indeed: this means that understanding the sign in one

place let you know the sign in all places. I'll remember using that

trick.

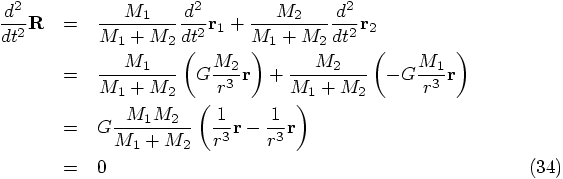

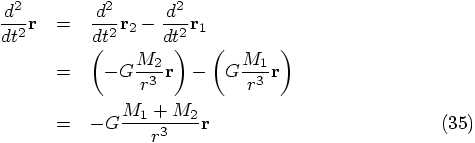

Okay, onward with the equations of motion. Given Eqs.(27)

and (33), we can calculate the accelerations for the

alternative coordinates by using the defining equations (17) and

(18), as follows.

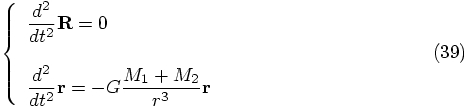

Dan: The second equation looks like a form of Newton's law of gravity,

but what does it mean that the first equation gives just zero as an answer?

Carol: Well, it seems that there is zero acceleration for the position

of the center of mass.

Dan: Ah, so the c.o.m. moves with constant velocity? But of course, that

is what we found in the one-dimensional case too.

Erica: Yes, and this means that we can choose an inertial coordinate

frame that moves along with the c.o.m., and in that coordinate frame

the center of mass does not move at all. And to make it really simple,

we can choose a coordinate frame where the c.o.m. is located at the

origin of the coordinates.

Dan: That does make life simple. In this coordinate frame, all the

information about the motions in the two-body problem is now bundled

in Eq. (35). It almost looks as if we are dealing

with a 1-body problem, instead of a 2-body problem!

Erica: Yes, this is what I meant when I announced that we could map

the two-body problem into an equivalent one-body problem, for any choice

of the masses. The original equations (27) and (33)

are coupled: both

A clear way to show this is to draw two separate figures,

Figs. 12 and 13. The c.o.m. vector

in Fig. 12 moves in a way that is totally independent of

the way the relative vector in 13 moves. The

c.o.m. vector moves at a constant speed, while the relative vector

moves as if it follows an abstract particle in a gravitational field.

To see this, notice that Eq. (35) is exactly

Newton's equation for the gravitational acceleration of a small body,

a test particle, that feels the attraction of a hypothetical body of

mass

Dan: Indeed. So the relative motion between two bodies can be described

as if it was the motion of just one body under the gravitational attraction

of another body, that happens to have a mass equal to the sum of the masses

of the two original bodies.

Erica: Exactly. And to complete this particular picture, we have to

make sure that the other body stays in the origin, at the place of the

center of mass. We can do this by giving our alternative body a mass

zero. In other words, we consider the motion of a massless test particle

under the influence of the gravitational field of a body with mass

Carol: I prefer to give it a non-zero mass. No material body can have

really zero mass. Instead, we can consider it to have just a very very

small mass. We could call it

Dan: If you like. I'm happy with the physical limit that Erica mentioned,

rather than the type of mathematical nicety that you introduced. Zero I can

understand. Because the test particle has zero mass, it exerts zero

gravitational pull on the central body. Therefore, the central body

does not move at all, and the only task we are left with is to determine

the motion of the test particle around the center.

And that is a one-body problem. Okay, I now see the whole picture.

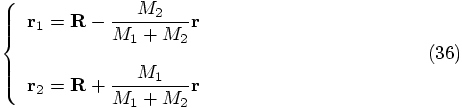

Carol: Let us gather the formulas we have obtained so far, for our

coordinate transformation, from absolute to relative coordinates.

Erica: Yes, and let me write the equation once again here:

4.1. Coordinates

will

also complete one orbit in the non-inertial coordinate system given

in fig. 13.

will

also complete one orbit in the non-inertial coordinate system given

in fig. 13.

. In each case, a single vector,

or equivalently the values of the components of that vector, describe

the position of one particle with respect to a point in space. For

example,

. In each case, a single vector,

or equivalently the values of the components of that vector, describe

the position of one particle with respect to a point in space. For

example,  describes the position of particle 2 with

respect to the origin, and

describes the position of particle 2 with

respect to the origin, and  describes the position of

particle 2 with respect to the point in space temporarily occupied by

particle 1.

describes the position of

particle 2 with respect to the point in space temporarily occupied by

particle 1.

, or equivalently, in the values

of their four components in two dimensions, or their six components in

three dimensions. But we can also describe the same two-body configuration

completely by giving the information contained in the pair of vectors

, or equivalently, in the values

of their four components in two dimensions, or their six components in

three dimensions. But we can also describe the same two-body configuration

completely by giving the information contained in the pair of vectors

.

.

and describing the same system through

specifying

and describing the same system through

specifying  .

.

-dimensional space, then a system of

two such vectors can also be represented as a single vector in a

-dimensional space, then a system of

two such vectors can also be represented as a single vector in a

-dimensional space. And then your second way of

speaking with respect to the

-dimensional space. And then your second way of

speaking with respect to the  -dimensional space boils

down to your first way of speaking with respect to the

-dimensional space boils

down to your first way of speaking with respect to the

-dimensional space.

-dimensional space.

or

or  ,

determines a single point in the direct product of two copies of the

base space in which the single vectors live. In our case, we have

started from two-dimensional vectors, so the space for pairs of

vectors is four-dimensional. And the coordinate transformation that

Erica has introduced is really a bijective mapping between two

four-dimensional spaces.

,

determines a single point in the direct product of two copies of the

base space in which the single vectors live. In our case, we have

started from two-dimensional vectors, so the space for pairs of

vectors is four-dimensional. And the coordinate transformation that

Erica has introduced is really a bijective mapping between two

four-dimensional spaces.

4.2. Equivalent coordinates

coordinate system

and the

coordinate system

and the  was bijective. What that means is

that any pair

was bijective. What that means is

that any pair  corresponds

to a unique pair

corresponds

to a unique pair  , and vice versa.

, and vice versa.

corresponds

to which pair of

corresponds

to which pair of  vectors.

vectors.

and

and  from

from

and

and  , with the definitions above.

But when we are given only

, with the definitions above.

But when we are given only  and

and  , can we

then really recover the original

, can we

then really recover the original  and

and  ?

?

and

and  as given, and the

question is how to derive the values for

as given, and the

question is how to derive the values for  and

and

.

.

and

and

instead of

instead of  and

and  for the

coordinate axes.

for the

coordinate axes.

.

.

,

pointing from the position of particle 1 to the c.o.m. This means that

we can reconstruct

,

pointing from the position of particle 1 to the c.o.m. This means that

we can reconstruct  as the sum of

as the sum of  and

and

!

!

must point, by

definition, in the opposite direction of

must point, by

definition, in the opposite direction of  . So you can

go from the old origin to

. So you can

go from the old origin to  by first following the

vector

by first following the

vector  from start till tip, and then following the

vector

from start till tip, and then following the

vector  , which conveniently starts at the tip

of

, which conveniently starts at the tip

of  . And the tip of

. And the tip of  lands on particle 1.

lands on particle 1.

, or in simpler

terms

, or in simpler

terms

?

?

because the new origin lies smack on the first particle,

so that particle has distance zero to the new origin. And the

position vector of the second particle is given as

because the new origin lies smack on the first particle,

so that particle has distance zero to the new origin. And the

position vector of the second particle is given as

.

Erica, your choice of coordinate frame shifting was brilliant! We have

in the new frame:

.

Erica, your choice of coordinate frame shifting was brilliant! We have

in the new frame:

that we found in

Eq.(21), we get:

that we found in

Eq.(21), we get:

4.3. Closing the Circle

we have

derived expressions for

we have

derived expressions for  . Then, starting

with

. Then, starting

with  we have derived expressions for

we have derived expressions for

. What more could you possibly want?!?

. What more could you possibly want?!?

to

to

and then back again to

and then back again to  .

.

. But, to be really sure, I'd like to finish

the job:

. But, to be really sure, I'd like to finish

the job:

4.4. Newton's Equations of Motion

, which in our

two-dimensional case can be written as

, which in our

two-dimensional case can be written as

pointing in the direction of the second

particle, as seen from the position of the first particle:

pointing in the direction of the second

particle, as seen from the position of the first particle:

,

since it is not used anywhere separately.

,

since it is not used anywhere separately.

. Notice that in this particular case

. Notice that in this particular case

. Therefore, the direction

. Therefore, the direction

is the opposite of the direction of

is the opposite of the direction of  ,

hence the minus sign.

,

hence the minus sign.

4.5. An Equivalent 1-Body Problem

and

and  occur in both

equations, indirectly through the fact that

occur in both

equations, indirectly through the fact that  .

In contrast, the equations (34) and (35) are

decoupled.

.

In contrast, the equations (34) and (35) are

decoupled.

. To check this, look at Eq. (22),

and replace

. To check this, look at Eq. (22),

and replace  by

by  and replace

and replace

by

by  .

.

, that is located in the center of the coordinate

system.

, that is located in the center of the coordinate

system.

, as mathematicians do

when they talk about something so small as to be almost negligible.

, as mathematicians do

when they talk about something so small as to be almost negligible.

4.6. Wrapping Up