5. Writing the Code

Carol:

Let's start coding! Which language shall we use to write a computer code?

I bet you physics types insist on using Fortran.

Erica:

Believe it or not, most of the astrophysics code I'm familiar with has

been written in C++. It may not be exactly my favorite, but it is at

least widely available, well supported, and likely to stay with us for

decades.

Dan:

What is C++, and why the obscure name? Makes the notion of an N-body

problem seem like clarity itself!

Carol:

Long story. I don't know whether there was ever a language A, but

there certainly was a language B, which was followed alphabetically by

a newer language C, which became quite popular. Then C was extended

to a new language for object-oriented programming, something we'll

talk about later. In a nerdy pun, the increment operation ``++'' from

the C language was used to indicate that C++ was the successor

language to C.

Dan:

But everybody I know seems to be coding in Java.

Carol:

Java has a clear advantage over C++ in being almost platform independent,

but frankly, I don't like either C++ or Java. Recently, I took a

course in which the instructor used a scripting language, Ruby.

And I was surprised at the flexible way in which I could

quickly express rather complex ideas in Ruby.

Erica:

Does Ruby have something like STL?

Carol:

You mean the Standard Template Library in C++? Ruby doesn't need any

such complications because it is already dynamically typed from

the start!

Dan:

I have no idea what the two of you are talking about, but I agree with

Carol, let's start coding, in whatever language!

Carol:

We want to write a simulation code, to enable us to simulate the

behavior of stars that move under the influence of gravity. So

far we have derived the equations of motion for the relative position

of one particle with respect to the other. What we need now is an

algorithm to integrate these equations.

Dan: What does it mean to integrate an equation?

Carol: We are dealing with differential equations. In calculus,

differentiation is the opposite of integration. If you differentiate

an expression, and then integrate it again, you get the same expression

back, apart from a constant. Our differential equations describe the

time derivatives of position and velocity. In order to obtain the

actual values for the position and velocity as a function of time, we

have to integrate the differential equation.

Erica:

And to do so, we need an integration algorithm. And yes,

there is a large choice! If you pick up any book on

numerical methods, you will see that you can select from a variety of

lower-order and higher-order integrators, and for each one there are

additional choices as to the precise structure of the algorithm.

Dan:

What is the order of an algorithm?

Erica:

It signifies the rate of convergence. Since no algorithm with a

finite time step size is perfect, they all make numerical errors.

In a fourth-order algorithm, for example, this error scales as the

fourth power of the time step -- hence the name fourth order.

Carol:

If that is the case, why not take a tenth order or even a twentieth

order algorithm. By only slightly reducing the time step, we would

read machine accuracy, of order

Erica:

The drawback of using high-order integrators is two-fold: first, they

are far more complex to code; and secondly, they do not allow arbitrarily

large time steps, since their region of convergence is limited. As a

consequence, there is an optimal order for each type of problem. When

you want to integrate a relatively well-behaved system, such as the

motion of the planets in the solar system, a twelfth-order integrator

may well be optimal. Since all planets follow well-separated orbits,

there will be no sudden surprises there. But when you integrate a

star cluster, where some of the stars can come arbitrarily close to each

other, experience shows that very high order integrators lose their edge.

In practice, fourth-order integrators have been used most often for the job.

Dan:

How about starting with the lowest-order integrator we can think of?

A zeroth-order integrator would make no sense, since the error would

remain constant, independent of the time step size. So the simplest

one must be a first-order integrator.

Erica:

Indeed. And the simplest version of a first-order integrator is

called the forward Euler integrator.

Dan:

Was Euler so forward-looking, or is there also a backward Euler

algorithm?

Erica:

There is indeed. In the forward version, at each time step you simply

take a step tangential to the orbit you are on. After that, at the

next step, the new value of the acceleration forces you to slightly

change direction, and again you move for a time step

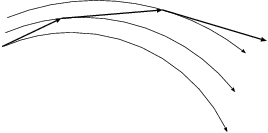

Figure 15: The forward Euler approximation is indicated by the straight arrows,

while the curved lines show the true solutions to the differential equation.

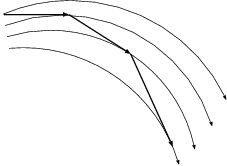

Figure 16: As figure 15, but now for the backward Euler approximation.

Carol:

Can't we do both, ie make half the mistakes of each of the two, while

trying to strike the right balance between forward and backward Euler?

Erica:

Aha! That is a good way to construct better algorithms, which then

become second-order accurate, because you have canceled the first-order

errors. Examples are second-order Runge Kutta, and leapfrog. We'll

soon come to that, but for now let's keep it simple, and stay with

first order. Here is the mathematical notation:

Carol: I have learned that in order to solve a differential equation,

you have to provide initial conditions.

Erica: Yes. It is like using a map: if you don't know where you are,

you can't use it. You start with the spot marked "you are here", and then

you can start walking, using the knowledge given by the map.

In our case, a differential equation tells you how a system evolves,

from one point to the next. Once you know where you are at time

0, the equation tells you where you will move to, and how, in

subsequent times.

So we have to specify the initial separation between the particles.

How about a simple choice like this?

Carol: Would it not be easier to use a position of

Erica: Well, as soon as we will do anything connected with the real

universe, we will have to go to 3D, so why not just start there, even

though the two-body problem is essential a 2D problem.

Dan: I don't care, either way, let's just move on. We have to translate

what Erica has just written into computer code. If it were Fortran, I would

start writing the first line as

Carol: In Ruby you do the same as in Fortran or C or C++, or Java for that

matter. In general, Ruby is designed around the `principle of least surprise.'

If you have some experience with computer languages, you will find

that whenever you encounter something new in Ruby, it is not too far

from what you might have guessed.

Erica: So assignment is exactly the same as in C?

Carol: The assignment itself is exactly the same, but there is no need to

declare anything.

Erica: Really? How does Ruby now that the variable x can hold a floating

point number and not, say, a character string or an array or whatever?

Carol: In Ruby there is no need for variable declaration, simply because

there is nothing to declare: variables have no intrinsic type. The type of

a variable is whatever you assign to it. If you write x = 3.14,

x becomes a floating point number; and if you then write x = "abs",

it becomes a string. This freedom and flexibility is expressed by saying

that Ruby is a dynamically typed language.

Erica: Isn't that dangerous?

Carol: I expected it would be, but in my experience, I in fact

made fewer mistakes using Ruby than using so-called strongly typed

languages, such as C and C++. Or stated more precisely: what mistakes

I made, I could catch far more quickly, since it would be rather

obvious if you assign pi = "abc" and then try to compute

2*pi*r and the like: you would get an error message telling

you that a string cannot be forced into a number.

Erica: so this means that we can just list the six assignments for

Carol: You can write several assignments on one line, separated

by semicolons, but I prefer to keep it simple and do it one per line.

Here they are:

By the way, does this specific choice of initial conditions mean that the

two particles will move around each other in a circle?

Erica: Probably not, unless we give exactly the right velocity

needed for circular motion. In general, the orbit will take the shape

of an ellipse, if the two particles are bound. If the initial speed

is too high, the particles escape from each other, in a parabolic or

hyperbolic orbit.

Dan: Starting from the initial conditions, we have to step forward in time.

I have no idea how large the time step step dt should be.

Carol: But at least we can argue that it should not be too large.

The distance dr over which the particles travel during a time step

dt must be very small compared to the separation between the two

particles:

Dan: In that case, we could take `much less than 1' to mean 0.1,

for starters.

Carol: I would prefer an even smaller value. Looking at fig. (15)

we see how quickly the forward Euler scheme flies off the tracks, so to speak.

How about letting `much less than 1' be 0.01? We can always make it

larger later:

Erica: We now know where we start in space, and with what velocity.

We also know the size of each time step. All we have to do is start

taking steps.

Dan: With a tiny time step of

Erica: That means we have to construct a loop. Something like `for

Carol: Let's have a look at the Ruby book. How do you repeat the same

thing k times? Ah, here it is. That looks funny! You write

k.times! So to traverse a piece of code

Dan: Surely you are joking! That is carrying the principle of least

surprise a bit too far to believe. How can that work? Can a computer

language really stay so close to English?

Carol: The key seems to be that Ruby is an object-oriented language.

Each `thing' in ruby is an object, which can have attributes such as

perhaps internal data or internal methods, which may or may not be

visible from the outside.

Dan: What is a method?

Carol: In Ruby, the word method is used for a piece of code that

can be called from another place in a longer code. In Fortran, you call

that a subroutine, while in C and C++ you call it a function. In

Ruby, it is called a method.

Erica: I have heard the term `object-oriented programming.' I really

should browse through the Ruby book, to get a bit more familiar with that

approach.

Dan: We all should. But for now, Carol, how does your key work?

Is the number

Carol: You guessed it! And every number has by default various methods

associated with it. One method happens to be called times.

Erica: And what times does is repeat the content of its argument,

whatever is within the curly brackets, k times, if the number is k.

Carol: Precisely. A bunch of expressions between curly brackets is

called a block in Ruby, and this block is executed k times. We will

have to get used to the main concepts of Ruby as we go along, but if

you want to read about Ruby in more systematic way, here is a

a good place to start, and here

is a web site specifically aimed at

scientific applications.

Dan: Amazing. Well, I would be even more amazed to see this work.

Carol: Let's test it out, using irb. This is an interactive program

that allows you to test little snippets of Ruby code. Let us explore what

it can do for us. You can invoke it simply by typing its name:

Dan: I like your prompt!

Carol: Well, I called my computer `gravity', and I set up my shell

to echo the name of my computer, so that's why it shows up here.

Dan: Quite appropriate. Now how do we interact with irb?

It seems that we can now type any Ruby expression, which will then be

evaluated right away. Let me try something simple:

Carol: Indeed. Time to test Ruby's looping construct:

Dan: ah, so c += 1 is the same as c = c + 1?

Carol: Yes. This is a construction used in C, and since taken over

by various other languages. It applies for many operators, not only

addition. For example, c *= d is the same as c = c * d.

Erica: This irb program is quite useful clearly, but I'm puzzled

about the various ways in which we can use Ruby. We are now writing

a Ruby program, by adding lines to a file, in just the same way we

would be writing a C or Fortran program, yes?

Carol: Yes and no. Yes, it looks the same, but no, it really is a

quite different approach. Ruby is an interpreted language, while C

and Fortran, and C++ as well, are all compiled languages. In Ruby,

there is no need to compile a source code file; you can just run it

directly, as we will see soon.

This, by the way, is why Ruby is called a scripting language, like

Perl and Python. In all three cases, whatever you write can be run

right away, just like a shell script. As soon as we have finished

writing our program, we will run it with the command ruby in

front of the file name, in the same way as you would run a cshell

script by typing csh filename. In our case we will type

ruby euler_try.rb.

Erica: So the difference is that in C you first compile each piece of

source code into object modules, and then you link those modules into

a single executable file, and then you run that file -- whereas in Ruby

the script itself is executable.

Carol: Exactly.

Erica: But what is the difference between typing ruby and typing

irb? If the ruby command interprets each line as it goes along,

what does irb add?

Carol: The difference is the i in irb, which stands for interactive.

In the case of irb, each line is not only interpreted, it is also

evaluated and the result is printed on the screen. In this way, you

can look into the mind of the interpreter, so to speak, and you can

follow step by step what is going on.

Dan: It sounds a bit like going into a debug mode.

Carol: I guess you could say that, yes. However, if you run a Ruby

script using the command ruby, you only get results on the screen

when you give a specific print command, such as print, as we will

see.

And just to give full disclosure, there is another hitch. If you are

starting to write a loop, say, you may have included an open parenthesis,

but not yet a closing parenthesis. In irb that is no problem; in fact,

the prompt will change, to indicate that you are one or more levels deep

inside nested expressions. But if you try to run such an incomplete file

with the ruby command, you will get an error message, even before the

Ruby interpreter starts.

Here is what happens. Upon typing ruby some-file.rb, a syntax

check is being carried out on the file some-file.rb. If the

parentheses are not balanced, a syntax error is produced, and the real

interpreter part of Ruby is not even started up.

Dan: Just like what happens in Fortran, when you get a compile error!

Carol: Yes, in a way. And to make things more confusing, many people

tend to call such an error a `compile error', even when working with

Ruby, even though in Ruby the code is not really compiled, strictly

speaking. The problem is that so-called compile errors in compiled

languages are really syntax errors; and interpreted languages can of

course have syntax errors as well. So when you hear someone telling

you `my Ruby (or Perl and Python) program didn't compile,' they mean

`my script had syntax errors.' However, strictly speaking, Ruby

initially parses the input program and transform it to a tree

structure, and then the interpreter actually traces this tree

structure, not the text string itself. So it is not entirely

incorrect to say that ruby first "compiles" a program. But this is

probably more than what you would want to know at this point.

Erica: All that is left for us to do is to write the content of the loop.

That means we have to describe how to take a single step forward in time.

Specifically, at the start we have to tell the particles how

to move to their next relative position, from our starting point of time

In addition, we have to tell the particles what their new relative velocity

using the acceleration vector

Dan: But we haven't calculated the acceleration a yet!

Carol: This is an important example of code writing, something called

`wishful thinking' or `wishful programming'. You start writing a code

as if you already have the main ingredients in hand, and then you go

back and fill in the commands needed to compute those ingredients.

Dan: That sounds like a top-down programming approach, which makes sense:

I like to start with an overview of what needs to be done. It is all too

easy to start from the bottom up, only to get lost while trying to put all

the pieces together.

Erica: To compute the acceleration, we have to solve the differential

equation for the Newtonian two-body problem, Eq. (42).

I will copy it here again:

Erica: Sure:

Carol: Let's see whether I remember my vector analysis class. The quantity

Erica: Indeed. The last quantity is a scalar because it is independent of

your choice of coordinate system. If we rotate out coordinates, the values

of

Dan: My Ruby book tells me that you must add the line

in order to use the square root method sqrt, where the term method

is used in the same way the word function is used in C and the word

subroutine is used in Fortran. The include statement is

needed to gain access to the Math module in Ruby, where

many of the mathematical methods reside.

Erica: Thanks! Now the rest is straightforward. To code up

Eq. (47), we first need to determine

Dan: Shall we see whether the program works, so far? Let's run it!

Erica: Small point, but . . . perhaps we should add a print statement,

to get the result on the screen?

Carol: I guess that doesn't hurt! The Ruby syntax for printing is

very intuitive, following the Ruby notion of the `principle of least surprise':

Erica: I like that principle! And indeed, this couldn't be simpler!

Dan: Apart from this mysterious \n at the end. What does that do?

Carol: It prints a new line. This notation is borrowed from the C language.

By the way, I'd like to see a printout of the position and velocity at the

start of the run as well, before we enter the loop, so that we get all the

points, from start to finish.

Erica: Fine! Here it is, our first program, euler_try.rb, which

is supposed to evolve our two-body problem for ten time units, from

t = 0 till t = 10:

5.1. Choosing a Computer Language

5.2. Choosing an Algorithm

for the usual double

precision (8 byte, i.e. 64 bit) representation of floating point numbers.

for the usual double

precision (8 byte, i.e. 64 bit) representation of floating point numbers.

in a straight line in that direction. Your approximate orbit is thus

constructed out of a number of straight line segments, where each one

has the proper direction at the beginning of the segment, but the

wrong one at the end.

in a straight line in that direction. Your approximate orbit is thus

constructed out of a number of straight line segments, where each one

has the proper direction at the beginning of the segment, but the

wrong one at the end.

and velocity

and velocity  of an individual particle,

where the index

of an individual particle,

where the index  indicates the values for time

indicates the values for time  and

and  for

the time

for

the time  after one more time step has been taken:

after one more time step has been taken:

. The acceleration induced on a particle by the

gravitational forces of all other particles is indicated by

. The acceleration induced on a particle by the

gravitational forces of all other particles is indicated by  .

So, all we have to do now is to code it up. By the way, let's rename

the file. Rather than a generic name nbody.rb, let's call it

euler.rb, or even better euler_try.rb. After all,

most likely we'll make a mistake, or two, or more, before we're finished!

.

So, all we have to do now is to code it up. By the way, let's rename

the file. Rather than a generic name nbody.rb, let's call it

euler.rb, or even better euler_try.rb. After all,

most likely we'll make a mistake, or two, or more, before we're finished!

5.3. Specifying Initial Conditions

axis

at a distance of one from the origin. The origin is the place where

the other particle resides, and it is the origin of the relative

coordinate system that we use. And the relative velocity is chosen to be

axis

at a distance of one from the origin. The origin is the place where

the other particle resides, and it is the origin of the relative

coordinate system that we use. And the relative velocity is chosen to be

in the direction of the positive

in the direction of the positive  axis.

This means that the initial motion is at right angles to the initial

separation.

axis.

This means that the initial motion is at right angles to the initial

separation.

and a velocity of

and a velocity of  ,

in other words, to work in two dimensions?

,

in other words, to work in two dimensions?

x = 1

Erica: That is how you would do it in C or C++ as well, although you first

would have to declare the type of x, by specifying that it is a number,

in our case a floating point number, even though we initialize it here

with an integer. The meaning of the equal sign, =, can be

interpreted as follows: the value of the right-hand side of the equation

gets assigned to the variable that appears at the left-hand side. In this

case, the value of the right-hand side is already clear, it is just 1,

and after execution of this statement, the variable x has acquired the

value 1.

and

and  ?

Like one line for each assignment?

?

Like one line for each assignment?

x = 1

y = 0

z = 0

vx = 0

vy = 0.5

vz = 0

and

and  , this means

, this means

.

.

5.4. Looping in Ruby

, we'll have to take

at least a hundred steps to see much happening, I guess. And to go a bit

further, say from time

, we'll have to take

at least a hundred steps to see much happening, I guess. And to go a bit

further, say from time  to time

to time  , we

will need a thousand steps.

, we

will need a thousand steps.

till

till  do something.' At least that

is how most computer languages express it. I wonder how ruby does it.

do something.' At least that

is how most computer languages express it. I wonder how ruby does it.

times,

you enclose that piece of code within the following loop wrapper:

times,

you enclose that piece of code within the following loop wrapper:

also an object?

also an object?

5.5. Interactive Ruby: irb

|gravity> irb

quit

and you can get out at any time by typing quit.

|gravity> irb

2 + 3

5

quit

Erica: How about going from arithmetic to algebra, by using some variables?

|gravity> irb

a = 4

4

b = 5

5

c = a * b

20

quit

I see. At the end of each line, the result of the operation is echoed.

And the value 20 is now assigned to the variable c.

|gravity> irb

c = 20

20

3.times{ c += 1 }

3

c

23

quit

Perfect! We started with 20 and three times we added 1.

5.6. Compiled vs. Interpreted vs. Interactive

5.7. One Step at a Time

to

to  , in our case. Or for a

general dt value, using the forward Euler approximation

(43), we obtain the position

, in our case. Or for a

general dt value, using the forward Euler approximation

(43), we obtain the position

at the end of the first step:

at the end of the first step:

x += vx*dt

y += vy*dt

z += vz*dt

should be. Using the same forward Euler construction, we can write:

should be. Using the same forward Euler construction, we can write:

vx += ax*dt

vy += ax*dt

vz += az*dt

.

.

is defined as

is defined as

:

:

is called a vector, and the quantity

is called a vector, and the quantity  is called

a scalar, right?

is called

a scalar, right?

and of

and of  and of

and of  may all change,

and therefore

may all change,

and therefore  will change. However,

will change. However,  will

stay the same, and that is a good thing: it denotes the physical distance

between the particles, something that you can measure. When two people use

two different coordinate systems, and both measure

will

stay the same, and that is a good thing: it denotes the physical distance

between the particles, something that you can measure. When two people use

two different coordinate systems, and both measure  , the value

they find had better be the same.

, the value

they find had better be the same.

,

and a simple way to do that is to write it as a product of two

express we have already found:

,

and a simple way to do that is to write it as a product of two

express we have already found:  :

:

r3 = r2 * sqrt(r2)

ax = - x / r3

ay = - y / r3

az = - z / r3

5.8. Printing the Result

print(x, " ", y, " ", z, " ")

print(vx, " ", vy, " ", vz, "\n")