1. First-Order Differential Equations

Bob: It has been a lot of fun, to derive so many different algorithms

and to implement them all in our two-body code.

Alice: Yes, I enjoyed it too, and I must admit, I learned a lot in the

process. But I still have the feeling that I'm missing some basic pieces

of insight. Do you remember how we struggled, trying to prove that the

Abramowicz and Stegun formula was correct, the fourth-order

Bob: But you figured it out, didn't you?

Alice: Well, yes, after a false start. And it was a bit alarming that

at first I didn't even realize that it was a false start. And to be

completely honest, even now I'm not a full hundred percent sure that

we got things right. Let me put it this way, I feel that I haven't

yet gotten a finger-tip feeling for what Runge-Kutta schemes are, and

how they really tick.

Bob: There must be several text books that you can look at. Surely they

will explain things in more depth than you want to know.

Alice: I did look at some books on numerical methods, but none of them

gave me what I really wanted to see. Some of them were just too

mathematical in their concern and notation, others didn't provide the

type of real detail that I wanted to see, yet others specialized on

particular approaches. What I really would like to see is a pedestrian

approach, no attempt to design special improvements. While I'm interested

in all the extras, from embedded higher-order schemes to using extrapolation

methods and symplectic schemes and what have you, I really would like to

first understand the basics better.

Bob: You mean, just the straightforward Runge-Kutta schemes of relatively

low order, without any extra bells and whistles?

Alice: Exactly. Here is an idea. If we limit ourselves to performing

at most two new force calculations per time step, things can't possibly

get too complex. Our Abramowicz and Stegun formula already had three

force calculations per time step, and I'm not suggesting that we explore

explicitly the whole landscape around that formula, at least not yet.

Bob: So you want to explore a smaller landscape, just to see in front of

your eyes how everything works. And while the simplest schemes, like

forward Euler and leapfrog, use only one new force calculation per

time step, you want to explore the full landscape of two new force

calculations per time step. Hmm, I like that. And I'm sure it would

be good for our students too, to see such an explicit survey.

Alice: I think so, but really, right now my main motivation is just for

myself to see exactly how those classical Runge-Kutta derivations are done,

from scratch, without taking anything on faith.

Bob: I like the idea, and I'm game. Where shall we start?

Alice: One problem for astronomers using books on numerical solutions

to differential equations is that most books focus on first-order

differential equations. In contrast, we typically work with

second-order differential equations, and often ones with special

properties. The gravitational equations of motion for the N-body

problem, for example, have a force term that is independent of time

and velocity.

This suggests to me that we should divide our work into two stages.

First we try to figure out how to solve a general first-order

differential equation, using up to two force calculations per step.

This will reproduce the results from the standard text books, no

doubt, but it will give us experience and will allow us to establish

a notation and a systematic procedure.

Then, in the second stage, we can cut our teeth on the gravitational

N-body system, to see what special methods will work there, and why,

and how. The Abramowicz and Stegun formula, for example, is tailored

already to second-order differential equations, albeit a general one

in which there is still a possible velocity dependence present in the

force calculations. We can go one step further, specializing to

position dependence only, and just see what spectrum of methods we

will find.

Then, with a bit of luck, we will have gained enough experience to be

able to look over the horizon, to get an idea what you could do with,

say, three new force calculations per step, which is the landscape

within which the Abramowicz and Stegun formula was grown.

Bob: A somewhat ambitious project, but still quite doable, I think.

You basically want to take the next step beyond forward Euler and

leapfrog, in any possible direction, and see the dimensionality of the

space of possible directions.

Alice: Something like that, yes. But let us restrict ourselves,

at least at first, to Runge-Kutta methods. This will mean no multi-step

methods, such as the original Aarseth scheme. It also means that we

won't use higher derivatives, such as the Hermite scheme. In addition,

we will exclude the use of implicit methods, which require iteration.

Bob: You could argue that, with two new force calculations per time step,

you should allow implicit schemes that have just one new force calcuation

per time step.

Alice: You could, even though it is not immediately clear that one iteration

will provide you sufficiently rapid convergence. Also, the resulting class of

implicit schemes is rather restricted. Perhaps we can look at that later.

For now, I really want to be austere and stay to the absolute basics.

Bob: Okay: explicit Runge-Kutta methods using up to two new force

calculations per time step, and no evaluations of jerks or anything else.

Alice: Let us start by choosing a specific notation.

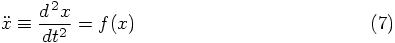

For the simplest form of differential equation, we can write:

Bob: Even though this is just a warming-up exercise, it would be nice to

give a physical interpretation to the first-order differential equation

that you wrote down:

Alice: In principle that is correct, but in practice, if we have a lot of

resistance, it is the velocity that is proportional to the force. If you

move a spoon through molasses, you have to push twice as hard to go twice

as fast.

Bob: But even in that case, the initial acceleration must still be

proportional to the applied force.

Alice: Yes, but only very briefly. As soon as you pick up a very small

amount of speed, friction starts to resist, canceling part of your force.

So after the initial transients die out, the velocity settles to a constant

value, proportional to the force you use. From than on, in the limit

of changes that are slow with respect to the duration of the transients,

the acceleration is proportional to the rate of change of the force,

not to the magnitude of the force.

Bob: I don't like the idea of posing a problem, and then neglecting the

interesting part of the solution, namely the transients.

Alice: So for once you are looking for a more clearly abstract model;

I thought you would like a quick and dirty physics example!

Bob: Molasses may indeed be too dirty for me. Why don't we stick with

considering

Alice: But the left hand side of the differential equation is a velocity.

The right-hand side has to be something else. In Newtonian dynamics

we have

Bob: Well, yeah, hmmm, let's see, that's not so clear.

Alice: Forgive the pun, but why don't we stick to molasses?

Bob: Ah, I got it! Hey, elementary, my dear Watson.

If a particle would be rolling down a potential well, without

any friction, the total energy would be constant. If we write

Bob: Okay, so we're talking now about a particle in a potential well.

Alice: You may, but I still prefer to talk about molasses, since in

that case we can make a more smooth transition to the case of a second

order differential equation.

Bob: I still prefer my interpretation. Let's just agree to disagree.

Alice: Fine with me, since, after all, the math will be the same.

Bob: Exactly. Okay, let's get to work. You have struggled with these

things a lot more than I have. How do we get started?

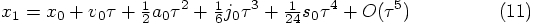

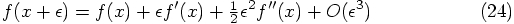

Alice: We want to check the quality of any given numerical approximation

scheme to the solution of our differential equation. In order to do

so, we can compare such a scheme with a Taylor series development of

the true solution, around the starting point of our one integration

step.

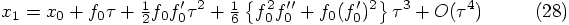

In other words, we can express the position at the end of one time step

in the following Taylor series:

By the way, here the acceleration comes out nicely as the rate

of change of the force applied, as would happen for a spoon moving

slowly through molasses.

Bob: That would take a lot of getting used to! For me, the acceleration

is just the rate of change of the velocity.

Alice: But isn't that a tautology? After all, the acceleration is

by definition the rate of change of the velocity, as a mathematical

construction. I thought we were trying to come up with a physical system

as an example.

Bob: But a potential well is surely a physical system! And what I thought

is that we had agreed to disagree.

Alice: I agree!

Bob: Me too. Coming back to our task,

I like the systematic approach idea, of using up to two

new force evaluations per time step. Well, this gives us two

choices: either one or two force evaluations.

Alice: Actually, there are four choices. In each case, we can try

to recycle a previous force calculation in the next step, or we don't.

Bob: You mean that you use the last force calculation, at the end of

a given step, as the first force value that you use for the next step?

Alice: Exactly. And this will put rather strict conditions on the

nature of that force calculation.

Bob: It means, of course, that a force calculation needs to take place

at the boundary of two steps, otherwise you can't recycle it. But that

doesn't seem to be a particularly severe restriction to me.

Alice: In principle, you could even recycle a force that is used in the

middle, if you would be willing to used the remembered values of the

previous step, you could still recycle. However, that would mean that

we would go beyond Runge-Kutta methods, and enter the area of multi-step

methods.

Bob: Let's not get into that, at least not know. I'd be happy to first

explore the landscape of Runge-Kutta algorithms. Okay, as long as we let

our last force calculation occur at the end of a step, we can recycle that

calculation for the next step.

Alice: Oh, no, it's not that simple. In a general Runge-Kutta approach,

you compute a few forces here and there, and only after doing that, you

combine those forces in such a way as to get a combination of them,

to give you a value of the new position accurate to high order.

Now the force that you would evaluate at that new position, at the

beginning of the next time step, will in general not be the same as

the force that you have calculated at the end of the current time step.

Even though it was evaluated at the same time, it will in general be

evaluated at a slightly different place. The reason is that at the

time of evaluation, you didn't yet have in hand the most accurate

estimate for the new position.

Bob: Hmm, that's tricky. I hadn't thought about that.

Alice: I hadn't either, until I started playing with some of those

schemes in detail. All the more reason to take a really pedestrian

approach, and just write everything out, to make sure we're not

overlooking something or jumping to conclusions!

To start with, let us not try to recycle any forces. Within that

category of attempts, we will first investigate what can happen when

we allow just one force evaluation per step, and then we will move

on to two force evaluations per step. After that, we'll look at

recycling.

Bob: Fair enough!

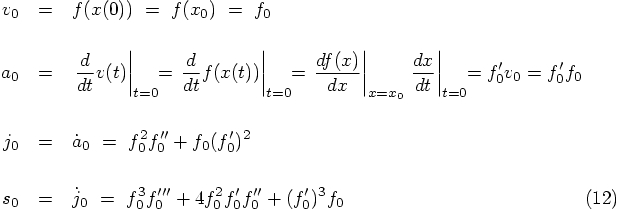

Alice: At the start of a time step, the only evaluation of the right-hand

side of the differential equation that is possible is the one at

We have no free parameter left, so this leads us to the

only possible explicit first-order integration scheme

Bob: Of course, forward Euler is the simplest possible scheme. It is

what anyone would have guessed, if they had guessed any scheme at all

Alice: That may be true, but I, for one, like to see a derivation for

any integration scheme, even the simplest and humblest of them all. It is

all nice and fine to say that something is intuitively obvious, but I am

much happier if you can prove that something is not only simple, but

actually the simplest, and under certain plausible restrictions, the only

one of its kind.

Bob: Can't argue about taste. I can see your point, but any good point

can be pressed to extremes. Well, as long as you do the calculating, I'll

sit back and relax.

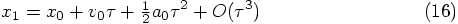

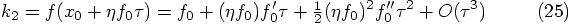

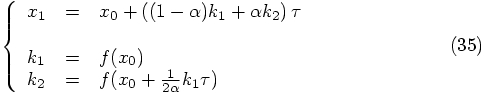

Alice: Now we can move to more interesting venues, when we allow

two force evaluations per step. After a first evaluation of the

right-hand side of the differential equation, we can perform a

preliminary integration in time, after which we can evaluate the

right-hand side again, at a new position:

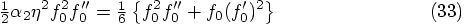

Alice: Yes. And since that Taylor series for

Bob: The main obstacle here is

Alice: The solution here is that we can develop

Bob: So we have to conclude that our scheme is only second-order

accurate. That makes sense: with one force evaluation, we got a

first-order scheme, and with two force evaluations, we get a

second-order scheme. Presumably with p force evaluations, you get a

scheme that is accurate to order p.

Alice: I would have guessed so too, but this is not so. Your guess

is correct for order 3 and 4, but it turns out that you need 6 force

evaluations to build an algorithm that is accurate to order 5!

Bob: That is surprising!

Alice: It is, until you realize that you get more and more equations that

you have to satisfy. The number of such conditions grows quite a bit

faster than the the number of force calculations. This is not yet obvious

in what we have done, but if will become obvious pretty soon. In general,

there are a lot of complicated combinatorial surprises in Runge-Kutta

derivations.

Bob: Fascinating. But for now, at least, it seems that going to higher

order gives us more freedom, rather than less. Unlike the first-order case,

we now have an extra parameter to play with.

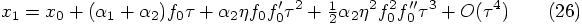

We started with three free parameters,

Alice: Well, let's check. If we define

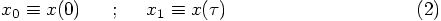

1.1. Starting at Square One

scheme that had a misprint in it?

scheme that had a misprint in it?

1.2. Keeping it Simple

1.3. Notation

the position and the

variable

the position and the

variable  the time. The solution of this equation is

given by

the time. The solution of this equation is

given by  . When we solve this equation numerically,

we use a finite time step

. When we solve this equation numerically,

we use a finite time step  . For now, we will analyze

the properties of the first time step. We choose

. For now, we will analyze

the properties of the first time step. We choose  at

the beginning of the first time step, and we denote the positions at

the beginning and end of the first time step by

at

the beginning of the first time step, and we denote the positions at

the beginning and end of the first time step by  and

and

, respectively:

, respectively:

1.4. A Matter of Interpretation

a force, but that doesn't seem

right. This equation tells us that the velocity is prescribed, and

equal to

a force, but that doesn't seem

right. This equation tells us that the velocity is prescribed, and

equal to  . A true force would give rise to an

acceleration, not a velocity.

. A true force would give rise to an

acceleration, not a velocity.

as a velocity.

as a velocity.

, which means that the acceleration is

proportional to the net force acting on the body. You now want to

have a velocity, but you have to specify what it is that is imposing

itself on your particle to produce that velocity.

, which means that the acceleration is

proportional to the net force acting on the body. You now want to

have a velocity, but you have to specify what it is that is imposing

itself on your particle to produce that velocity.

for the potential energy per unit mass, and

for the potential energy per unit mass, and

for the total energy per unit mass, then the velocity

can be expressed as:

for the total energy per unit mass, then the velocity

can be expressed as:

a force from the beginning.

a force from the beginning.

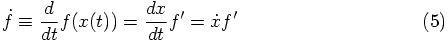

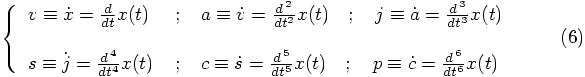

1.5. Taylor Series

1.6. New Force Evaluations

1.7. One Force Evaluation per Step

:

:

after we take one step? Let us

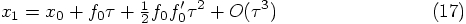

see how well we can match Eq. (15) with Eq. (17),

in successive powers of

after we take one step? Let us

see how well we can match Eq. (15) with Eq. (17),

in successive powers of  .

The constant term

.

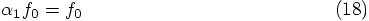

The constant term  matches

trivially, and our first condition arises

from the term linear in

matches

trivially, and our first condition arises

from the term linear in  :

:

term in

Eq. (17):

such a match would require

term in

Eq. (17):

such a match would require  ,

which is certainly not true for general force prescriptions.

,

which is certainly not true for general force prescriptions.

1.8. Two Force Evaluations per Step

. The coefficient

for each term is, as yet, arbitrary, so let us parametrize them as

follows:

. The coefficient

for each term is, as yet, arbitrary, so let us parametrize them as

follows:

is defined

as a series in

is defined

as a series in  , we must somehow translate the above

expressions, too, a series in

, we must somehow translate the above

expressions, too, a series in  , around

, around  .

.

,

which itself involves an expression that depends on

,

which itself involves an expression that depends on  .

.

itself in a Taylor series around

itself in a Taylor series around  . In general,

for any function of , we can write the Taylor series for a position

. In general,

for any function of , we can write the Taylor series for a position

near

near  as:

as:

, we have to insist that

, we have to insist that

, we would like to satisfy:

, we would like to satisfy:

? This would require

? This would require

, this would require that

, this would require that  ,

which is not true for general force prescriptions.

,

which is not true for general force prescriptions.

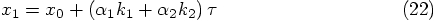

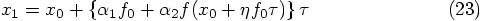

1.9. A One-Parameter Family of Algorithms

,

,

, and

, and  . Since we only have the

two boxed conditions above, we can expect to be left with one degree

of freedom in choosing the coefficients in our algorithm.

. Since we only have the

two boxed conditions above, we can expect to be left with one degree

of freedom in choosing the coefficients in our algorithm.

, we find:

, we find:

, leading to:

, leading to:

, which gives:

, which gives:

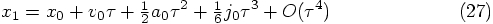

, we effectively average the

evaluations at the beginning and at the end of the trial step, and you

can imagine that this gives you one extra order of accuracy, since you

effectively cancel the types of error you would make if you were using

a force calculation only at one end of the step.

, we effectively average the

evaluations at the beginning and at the end of the trial step, and you

can imagine that this gives you one extra order of accuracy, since you

effectively cancel the types of error you would make if you were using

a force calculation only at one end of the step.

, we use the evaluation at the

end of a smaller trial step that brings us approximately mid-way

between the beginning and the end of the step. Then, at that point,

we again obtain an estimate for the average of the forces at begin and

end of the time step.

, we use the evaluation at the

end of a smaller trial step that brings us approximately mid-way

between the beginning and the end of the step. Then, at that point,

we again obtain an estimate for the average of the forces at begin and

end of the time step.