1. Setting the Stage

Alice: So here we are, ready to begin writing a toy model to simulate

a dense stellar system. We have decided to begin with a very simple

integrator, since we will use the material in a course for students

with little or no prior background in differential equations and

numerical methods.

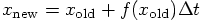

Bob: That pretty much defines the first integrator to discuss: one

based on the forward Euler integration scheme. To take one step, you

add to each variable its derivative multiplied by the value of the

time step. In other words, you just step forward by incrementing each

variable by its derivative, as specified by the differential equation.

Alice: The only way to make that sentence clear to someone with little

experience in this area is to give an example. So let's code it up.

Bob: We decided to do this in Ruby, but neither of us have any

background in the language. To get started, I had a look at an

introductory book, yesterday evening. It is called Programming Ruby

by Dave Thomas and Andy Hunt, a.k.a. the Pragmatic Programmers. I found

it quite useful, and it is also well written.

Alice: I'll have a look at it then as well. Did you find enough to get

started?

Bob: I guess so. Let's try and see. Before getting to gravity

and equations of motion, how about building a simple skeleton first,

something that just reads in the data and prints them out, without

doing any integrating?

Alice: But before doing that, we need to decide upon a data format.

Let's not get too fancy, for now. How about just listing for each

particle the seven numbers on one line: mass, position, and velocity,

with the latter two each being a three-dimensional vector, and

therefore with three components each?

Bob: Well, in that case, let's start with an even simpler problem,

with reading and writing the data for a single particle. For an

object oriented language like Ruby, that suggests that we create a

class Body for a particle in an N-body system.

Alice: Can you remind me what a class is?

Bob: I thought you were going to tell me, while pointing out how

important they are for your obsession with modular programming!

Alice: Well, yes, I certainly know the general idea, but I must

admit, I haven't really worked with object oriented languages very

much. At first I myself was stuck with some existing big codes that

were written in rather arcane styles. Later, when I got to supervise

my own students and postdocs, I would have liked to let them get a

better start. However, I realized that they had to work within rather

strict time limits, within which to learn everything: the background

science, the idea of doing independent research, learning from your

mistakes, and so on.

The main problem for my students has been that there is hardly any

literature that is both interesting for astrophysicists and inspiring

in terms of a really modern programming attitude. When students are

pressed for time and eager to learn their own field, they are not

likely to spend a long time delving into books on computer science,

which will strike them as equally arcane, for different reasons, as

the astrophysical legacy codes.

Given that there was no middle ground, I did not want them to focus

too much on computational techniques, because that would have just

taken too much time. My hope is, frankly, that our toy model approach

will bridge this huge gap, between books that are clear but of very limited

use, and codes that are useful but of very limited clarity.

Bob: You seem to find a way to introduce a world wide vision for

every small task that you encounter. As for me, I'm happy to just

build a toy model, and if students will find it helpful, I'd be happy

too. But just to answer your question, defining a class is just a way

to bundle a number of variables and functions together. Just like a

number of scalar values can be grouped together in one array, which

can stand for a physical vector for example, you can group a more

heterogeneous bunch of variables together. You do this mainly for

bookkeeping reasons, and to keep your program simpler and more robust.

In practice, a good guide to choosing the appropriate class structure

for a given problem is to start with the physical structures that

occur naturally, but that may not always be the best option, and

certainly not the only one.

Bob: For example, a single particle has as a minimum a mass,

a position and velocity. Whenever you deal with a particle, you

would like to have all three variables at hand. You can't put them in

a single array, because mass is a scalar, and the other two variables

are vectors, so you have to come up with a more general form of

bundling.

The basic idea of this kind of programming is called object-oriented

programming. In many older computer languages, you can pass variables

around, where each variable can contain a number or an array of numbers;

or you may pass pointers to such variables or arrays. In an

object-oriented programming language, you pass bundles of information

around: for example all the information pertaining to a single

particle, or even to a whole N-body system. This provides convenient

handles on the information.

If you look in a computer science book, you will read that the

glorious reason for object-oriented programming is the ability to make

your life arbitrarily difficult by hiding any and all information

within those objects, but I don't particularly care for that aspect.

Alice: I do think encapsulation has its good sides, but we can come

back to that later. What exactly is it that you can put inside an object?

I guess an object can contain internal variables. Can it contain

functions as well?

Bob: To take the specific case of Ruby, a typical class contains both.

For a class to be useful, at least you have to be able to create an

instance of a class, so you need something like what is called a

constructor in C++. In the case of Ruby, like in the case of C++, you

have the freedom to define an initializer, through which you can

create an instance of a class with your desired values for the

internal variable. Or you can choose not to define an initializer,

that is fine too.

Note as a matter of terminology that what I have called a function, or

what would be called a subroutine in Fortran, is called a method in

Ruby. There are other objects in Ruby, besides classes. Sometimes

you have a group of functions that are either similar or just work

together well, and you may want to pass them around as a bundle. In

Ruby, such bundles of functions are called modules. But to get

started, it is easier to stick to classes for now.

Alice: Ah, that is nice! Does this mean that we can define an

integration algorithm as a module, independent of the particular

variables in the classes that define a body or an N-body system? I

mean, can you write a leapfrog module that can propagate particles,

independently of their type? You could have point particles in either

a two-dimensional of a three-dimensional world. Or you could have

particles with a finite radius, that stick together when they collide;

as long as they are not too close, they could be propagated by the

same leapfrog module.

Bob: You really have an interesting way of approaching a problem.

We haven't even defined a single particle, and you are already

thinking about general modules that are particle independent. I

suggest we first implement a particle. I think this is how we

can introduce a minimal class for a single particle:

In a few minutes, we can go through the precise meaning of these

constructs, but here is the general idea: you can give three arguments

in a call to initialize, to specify the mass, position, and velocity.

If you don't specify some of these arguments, they will acquire the

default values that are given here by all the zeroes in the first line

of the definition of initialize. The next line assigns these values

to internal variables that have names starting with a @ sign.

Alice: That is remarkably short and simple! In fact, it seems too

simple. I am surprised that we do not have to declare the internal

variables. In other languages that I am familiar with, it is

essential that you tell the computer which memory places to set aside

before naming them.

Bob: Ruby is dynamically typed. This means that the type of a

variable is determined at run time. In other words the type of a

variable is simply the type of the value that is assigned to a

variable.

Alice: And you can change the type of that value, whenever you want?

Can we try that? I'd like to see the syntax of how you do that.

Bob: Before we do that, just one thing: staring at this amazingly

simple class definition makes me realize both how similar it is to

what you would write in C++, and how different.

Alice: Indeed, the logical structure of C++ class definitions

is very similar.

Bob: But the big difference is that a C++ class definition

is quite a bit longer.

Alice: I'm curious how much longer. Do you remember how to write a

similar particle class in C++?

Bob: That shouldn't be too hard. Always easiest to look at an

existing code. Ah, here I have another C++ code that I wrote a while

ago. Okay, now I remember. Of course. Here is how you do it in

C++:

Alice: That is quite an impressive difference, between Ruby and C++!

But aren't you cheating a bit? That last part, with the main function

down below, does not occur in your short and sweet Ruby class definition.

Bob: It doesn't occur there, because you don't need it. All that

main does for you is create an object and then printing its internal

values. You can let Ruby do that for you without even asking for it.

Here is what you do. The easiest way to work with Ruby is to use the

command irb. The acronym stands for interactive Ruby. You

invoke it by simply typing irb on the command line. Now as soon as

you create an instance of a class in Ruby, the interpreter echoes the

content to you, for free!

Alice: I'll try it out. But rather than wrestling with a whole

particle, I prefer to start with a single variable, to see how Ruby

functions at its most basic level. Also, remember that I asked you

whether you can change the type of the value of a variable, whenever

you want? I want to see that for myself. One thing at a time!

Let me introduce an identifier id. I will first give it a numerical

value, and then I will assign to it a string of characters, to give it

a name. Since Ruby is friendly enough not to insist on declaring my

variables beforehand, I presume I can just go ahead and use id right

away.

Bob: Just like in C, variables are not the only things that have values.

In fact, every expression has a value. And irb makes life more

clear by echoing the value of each line as soon as you enter it.

Alice: I like that. It will make debugging a lot easier. Okay, let

me try to change the type of id.

Alice: But that line works fine when I write shell scripts. Since Ruby

is called a scripting language, I thought it might work here too.

Bob: Each scripting language has different conventions. In your shell

case, I bet you have to invoke the value of a variable cat by typing

$cat, each time you use it. Ruby has another solution: typing

cat echoes the value of cat. When you want to introduce a string

consisting of the three letters c, a, and t, you type "cat".

Alice: Here goes:

Bob: Indeed. And at any time you can ask Ruby what the type of

your dynamically typed variable currently is. Any variable is an

instance of some class. And the class it belongs to in turn has a

method built in, not surprisingly called class, which tells you the

type of that class. In Ruby, you invoke a method associated with a

variable by writing that variable followed by a period and the method

name.

Alice: I find it surprising, if you ask me; I would have expected

something like type. But I'll take your word for it.

Bob: And since you only give the definition of Body without yet

creating any of its instances, there is no value associated with it.

Here nil means effectively `undefined'.

Alice: But we have just defined the Body class; why does Ruby

claim it is undefined?

Bob: In Ruby, the definition of a class does not return a value,

since there is no reasonable answer that can be given to a non-existent

question. But since the interpreter wants to echo something, it just

returns, `nil' as meaning an undefined value, or literally nothing.

And this has nothing to do with the definition of a class. This may

sound more complicated than it is, but it is quite logical.

Alice: I see, yes, that makes sense. So the class Body has only

one function, starting with def and ending with the inner end,

correct?

Bob: Indeed. And the last end is the end of the class definition,

that starts with class Body. Note the grammatical rule that

the name of a class such as Body always starts with a capital

letter. The names of normal variables, in contrast, start with a

lower case letter: we have three such variables, mass, pos, and

vel. All three are given here as possible parameters to the

initialization function initialize. 1.1. Ruby

1.2. A Body Class

##include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class body

{

private:

double pos[3];

double vel[3];

double mass;

public:

body(double inmass, double inpos[3], double invel[3]){

mass = inmass;

for(int i=0;i<3;i++){

pos[i] = inpos[i];

vel[i] = invel[i];

}

}

void print(){

cout << mass <<endl;

cout << pos[0] <<" "<< pos[1] <<" "<< pos[2] <<endl;

cout << vel[0] <<" "<< vel[1] <<" "<< vel[2] <<endl;

}

};

main()

{

double zero3[3]={0.0,0.0,0.0};

body x = body(0.0,zero3,zero3);

x.print();

}

1.3. The irb Interpreter

|gravity> irb

irb(main):001:0> id = 12

=> 12

And as you predicted, a value gets produced magically. But where does

that come from?

irb(main):002:0> id = cat

NameError: undefined local variable or method `cat' for main

:Object

from (irb):2

Bob: Ah, Ruby treats your cat in an equally friendly way as

your id, assuming it is itself a name of a variable (or a method),

rather than a content that can be assigned to a variable.

irb(main):003:0> id = "cat"

=> "cat"

It worked! And presumably id has now forgotten that it ever was a

numerical variable.

irb(main):004:0> id.class

=> String

irb(main):005:0> id = 12

=> 12

irb(main):006:0> id.class

=> Fixnum

Hey, that is nice! You can immediately check what is going on.

Let's see what happens when I type in the text of the Body class

declaration above.

irb(main):007:0> class Body

irb(main):008:1> def initialize(mass = 0, pos = [0,0,0], vel = [0,0,0])

irb(main):009:2> @mass, @pos, @vel = mass, pos, vel

irb(main):010:2> end

irb(main):011:1> end

=> nil

I see another nice feature. I had been wondering about the meaning of

the :0 after each line number. That must have been the level

of nesting of each expression. It goes up by one, each time you enter

a block of text that ends with end.